Where ash-fall is an everyday occurrence

Have you ever imagined living next to—or even on—an active volcano? For the people of Kagoshima, Japan, this is part of daily life.

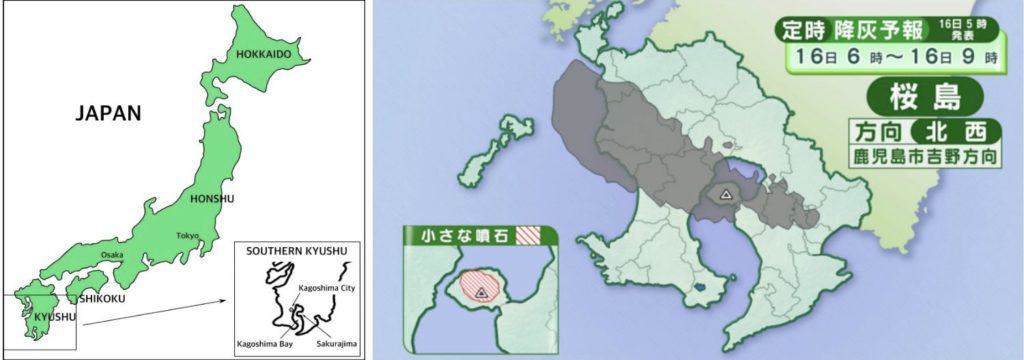

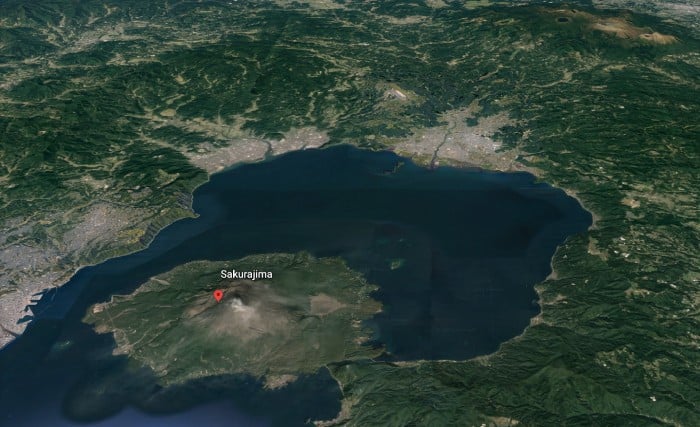

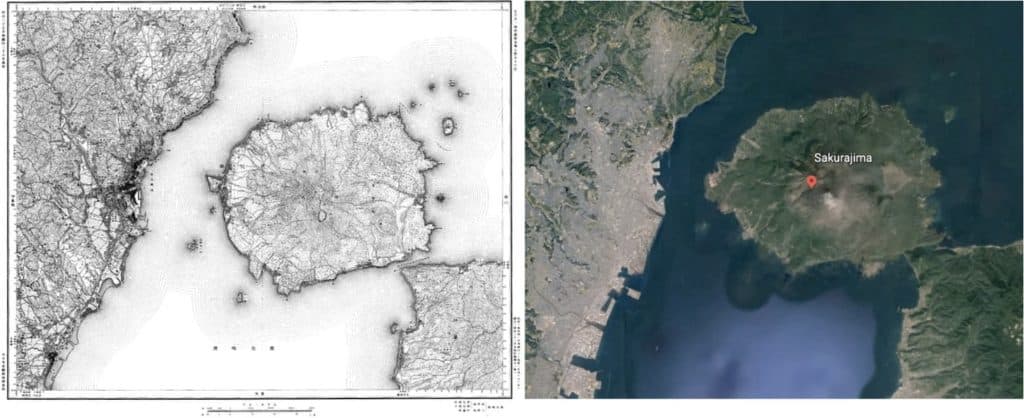

Sakurajima is an active stratovolcano four kilometers across Kagoshima Bay from downtown Kagoshima City, in southern Japan. Although its name means “cherry blossom island,” it is no longer an island as a result of a major eruption in 1914.

Sakurajima is one of the most active volcanoes in the world. Between 2009 and 2015, it averaged more than 1,000 eruptions each year. In 2020, it calmed down to a reasonable—for local residents—432 eruptions.

Despite its frequent eruptions, Sakurajima has been inhabited since ancient times. Archaeologists have uncovered shell heaps—piles of discarded shells and food waste—dating back to the Jomon Era (14,000–600 BC in southern Kyushu), evidence of early human settlement.

Before the major eruption of 1914, more than 20,000 people lived on Sakurajima. Today, that number has declined to around 4,000, largely due to Japan’s shrinking population, a trend that most severely affects rural areas. Fewer than 100 elementary school children live on the volcano. They wear helmets to and from school to protect themselves from falling ash and pumice.

Residents of Kagoshima City sweep volcanic ash from streets and sidewalks daily. The ash is put in yellow ash bags provided by the government and placed at designated collection centers in each neighborhood.

A low-cost ferry runs every 15 minutes between Sakurajima and downtown Kagoshima, making the 10-minute trip easy and convenient. For Sakurajima residents, access to higher education, jobs, shopping, and restaurants in the city is always within reach.

Living with ashfall

Each morning, Kagoshima residents check the weather report—not just for rain or sunshine, but to see the predicted areas of ashfall. This daily habit helps them decide whether to open windows, hang out laundry, or wash their cars. In my experience, washing the car all but guarantees ash the next day.

When ashfall is heavy, cars use windshield wipers and people wear masks and carry umbrellas to shield themselves. Sweeping up ash is part of life—as normal as washing laundry.

Geology

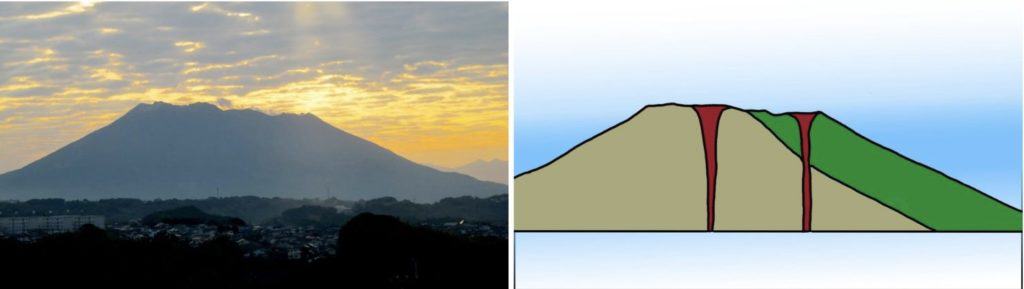

Sakurajima is actually two volcanoes that formed side by side along a north-south axis. It sits on the southern rim of the Aira Caldera, the vast remains of a supervolcano that erupted approximately 30,000 years ago.

That ancient eruption left a lasting mark on the region. It produced the deep layer of white, pumice-rich soil known as shirasu, which covers much of southern Kyushu. The massive release of magma caused the ground to collapse, forming the Aira Caldera. Seawater rushed in, filling the depression and creating what is now the northern half of Kagoshima Bay. Underneath the bay is a large magma chamber that feeds Sakurajima and is responsible for its ongoing volcanic activity.

The northern peak (to the left in the pictures) is the oldest and is inactive. Over time, erosion from this peak created a fertile alluvial fan on the volcano’s eastern side. This well-drained soil supports the cultivation of Sakurajima’s famous agricultural products: the world’s largest radishes and the world’s smallest oranges.

The southern peak, by contrast, is younger and still active. It is from this side that ash, gas, and pumice regularly spew.

Taisho Eruption, 1914–1915

On January 10, 1914, Sakurajima and the surrounding areas were shaken by four strong earthquakes. The next day, 250 smaller quakes occurred. The 23,000 people who lived on the island literally felt what was coming. Using whatever boats they could get their hands on, the islanders worked together to evacuate themselves and their farm animals safely to Kagoshima City. The Imperial Navy provided more ships the next day.

At 10:05 on January 12, a fissure opened halfway up the southwestern flank of the volcano facing the city across the bay. Ash, pumice stone, and gas thundered out horizontally, then shifted to spiraling upwards. The roar of this explosion was heard all across the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku. This eruption was soon joined by another opening on the eastern flank of the volcano, violently ejecting ash and gas.

By 11:00, these two plumes had risen five to eight kilometers into the atmosphere, and within days the ashfall had reached all of Kyushu, and as far away as Osaka, Tokyo, and even the Bonin Islands, more than 1,000 kilometers southeast of Kyushu.

On the night of January 12, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake occurred, centered beneath Kagoshima Bay. This quake broke the seismograph in Kagoshima City, collapsed houses, caused a tsunami, and killed 35 people. Ash and pumice continued falling.

Yet another large earthquake occurred on January 13, bringing with it lava flowing from both east and west vents. Along with continued ash and pumice eruptions, lava flowed for months, burying fields and villages, shallowing Kagoshima Bay, and covering nearby islands.

As the flow continued, parts of the bay heated to more than 750°C, cooking fish and other sea life. Rafts of pumice stones intermingled with dead sea creatures bobbed on the surface and washed up on the shore.

By January 13, the people of Kagoshima City had also been evacuated. Aid came from the Japanese government and other nations. The destruction that was caused by the volcano was significant, although few lives were lost.

Through the months of ash and pumice fall, large areas of farmland were buried, thousands of buildings were destroyed, and people’s livelihoods were shattered.

With the wind blowing from the west, houses on the Osumi peninsula, east of the volcano, were buried up to the roofs in ash. Many houses in Kagoshima City to the west that had survived the 7.1 magnitude earthquake, collapsed under the weight of the ashfall.

By early April 1914, Sakurajima was no longer an island. The lava flow had filled in the Seto Straight that had divided Sakurajima from the Osumi peninsula, connecting the island to the mainland.

Eruptions continued sporadically, decreasing in frequency over the next year. By November 1915, the volcano was quiet. The residents of Sakurajima were provided with money by the government, and more than half of them returned to their ancestral homes.

After the eruption subsided, it was discovered that the entire area had sunk about 60 centimeters—in some places, as much as a meter. The lava that had been stored under the bay in the magma chamber of the Aira caldera had been released and the land above it sunk.

Preparing for the next big eruption

About ten kilometers beneath the bay, the once-emptied magma chamber has been slowly refilling. Today, researchers monitoring the volcano report that the amount of accumulated magma is roughly equal to what had built up before the 1914 eruption. They predict that an eruption of similar scale could occur by 2030.

Knowing the inevitability of future devastating eruptions, local and national governments have taken steps to try to lessen their impact and improve early warning capabilities.

Canals for channeling mudslides and lava have been built on the slopes of Sakurajima, and each January, evacuation drills are held for the entire population.

The tiniest rumblings, changes in the volume of the magma pool, and increases in the size of the volcano are carefully monitored by high-tech equipment on Sakurajima. The data is analyzed by specialists in Kagoshima and at Kyoto and Tohoku Universities, and appropriate warning levels are announced.

How would you feel about living on or near an active volcano?

All photos ©Diane Tincher unless otherwise specified.

Sources:

Sakurajima eruption data, population statistics, Taisho eruption, more on the Taisho eruption, geology, general information from Sakurajima Visitors’ Center, and 26 years of living in Kagoshima City.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/