Japan’s healthiest spirit

When visitors come to Kagoshima and ask me to recommend a good local sake, I hesitate. While Kagoshima does produce some sake, its true specialty is shochu, which has been distilled here since even before the humble sweet potato arrived in the early 18th century—a crop that would later become a lifesaver and the star ingredient of its premier shochu.

Shochu’s Beginnings

To uncover the origins of shochu’s story, I visited Koriyama Hachiman Shrine in Okuchi Town, located in northern Kagoshima Prefecture. During renovations done in 1954, workers discovered sumi ink writing on the underside of a shingle bearing the date 永正4年, or 1507, leading scholars to conclude that the shrine must have been built before that year.

The shrine’s architecture blends techniques from the Muromachi and Momoyama periods with distinct Ryukyuan influences. In 1949, the main shrine building was designated a National Important Cultural Property. See the beautiful Ryukyu-style pillars below.

But I digress.

You might wonder why I would visit a shrine in my quest to learn more about shochu. The answer lies in the unexpected piece of history found in writing hidden inside the northeast decorative head beam—ancient graffiti scrawled in complaint: “Despite our daily hard work, the head priest here never once gave us shochu to drink. What a cheapskate!”

The carpenter’s 1559 gripe leaves us with the first written mention of “shochu” in Japanese history, marking Okuchi as the birthplace of shochu.

The shochu the disgruntled carpenter longed for would likely have been made from grains, perhaps rice, and is thought to have evolved from awamori, a distilled beverage of the Ryukyu Islands. The islanders are believed to have learned their distillation technique through trade with Siam (modern-day Thailand) in the 15th century. The process involves soaking rice, fermenting it with black koji mold and yeast, and then distilling it once.

The Ryukyu court prized awamori so highly that they reserved century-old vintages for honored guests. Today, Okinawans still produce awamori, which is classified as a type of shochu, although much stronger at 50–86 proof (25–43% alcohol).

It wasn’t until the 18th century that shochu started to be made from sweet potatoes, thanks to the sweet potato god, Maeda Riemon. (May he never be forgotten.) Sweet potatoes grow like weeds in Satsuma, today’s Kagoshima, and soon became a staple of the diet—and the distillery.

How Shochu is Made

Like sake production, shochu begins by steaming rice, cooling it, and inoculating it with white koji mold spores, Aspergillus oryzae. This rice is left in a 40-42˚C room for 40 hours for the mold to grow. As the koji works its magic, workers must turn and spread the rice every two hours around the clock. They crumble the clumps of rice that form due to the koji growth to keep the mold growing evenly.

About Koji

There are three types of koji mold: black, white, and yellow. While awamori uses only black, shochu can use all three types, with white being the most common. Yellow koji is harder to use in the warm climates of Kyushu and Okinawa, so it is seldom used. It is, however, the standard koji used in making sake, or nihonshu.

The transformed koji rice is then mixed with water and yeast to make moromi mash. Over three to eight days, the koji enzymes convert starch to sugar, the yeast feeds on the sugar, and the mash gradually acidifies to a pH of 3.5—about as tart as a ripe strawberry.

Next, the base ingredient, let’s use sweet potatoes, is steamed and added to the moromi mash with additional water. This is left to ferment for about two weeks, allowing the earthy sweetness of the potatoes to meld with the bright acidity of the mash.

The fermented mash is then distilled. Gently heated below water’s boiling point, the alcohol and aromatic compounds vaporize, travel through a condenser, and emerge as a clear spirit with 37–40% alcohol. This method was used for centuries. Then, in the 1970s, an enterprising Fukuoka producer pioneered vacuum distillation—extracting alcohol at lower temperatures to create lighter, floral flavor. This innovation catapulted shochu to nationwide popularity.

Freshly distilled shochu is then filtered and aged in tanks, earthenware pots, or bottles at full strength, around 40% alcohol by volume. After aging from months to years, pure water is added to lower the alcohol to a smooth 20–25%, and the final product is bottled.

Categories of Shochu

Honkaku

To be classified as honkaku, authentic, shochu must be distilled only once in a traditional pot still, like those used for whiskey. This method preserves the aromas and flavors of its base ingredients, which can range from Satsuma sweet potatoes to Amami Oshima black sugar, sake lees, rice—or any of 49 other officially approved raw materials.

Kōrui

Kōrui shochu undergoes continuous distillation in a column still, similar to vodka production. Made from inexpensive cereals or molasses, its repeated distillations strip away distinctive flavors, resulting in a clean, neutral spirit. Its affordability and versatility make it a staple for mixed drinks and for making ume-shu, so-called “plum wine” that is actually apricot-infused shochu.

Awamori

Made exclusively with black koji mold and long-grain indica rice—a legacy of the trade of the former Ryukyu Kingdom—awamori carries deeper umami and tropical fruit notes. Many premium awamori varieties are aged for decades in clay pots, developing a complexity akin to fine rum.

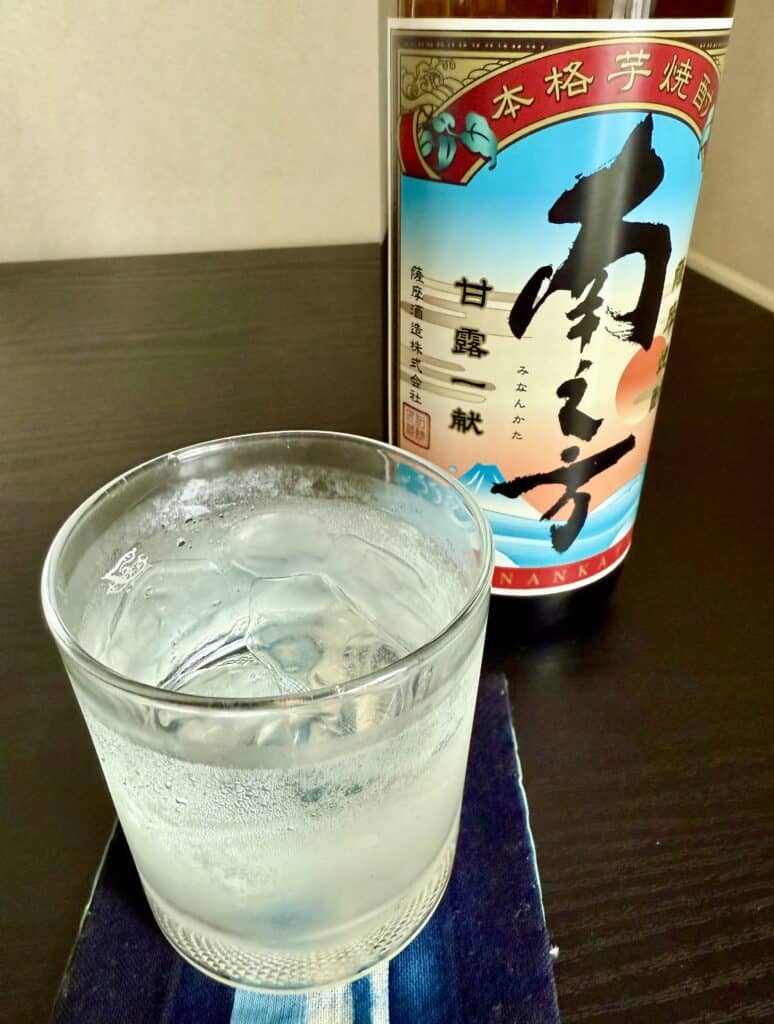

How to drink shochu

Shochu lends itself to a wide variety of drinking methods. It’s a great base for cocktails, or simply mixing with juice or tea. It can be drunk straight, on the rocks, mixed with soda water, cold water, or hot water.

In Kagoshima, the most common way to drink shochu is oyu-wari—mixed 6:4 or 7:3 shochu to hot water (70°C/158°F). This brings the alcohol content down to a smooth 15-17%. To fully appreciate the aroma of fine shochu, locals tell me that hot water should always be poured first before adding the shochu.

Why drink shochu?

✓ Zero carbs, zero sugar, zero gluten

✓ Only 35 calories per 2-oz serving (vs 140 in vodka, 160 in whiskey)

✓ Low congeners and high purity reduce hangover risk

But that’s not all!

Shochu’s health benefits

Experiments done by Dr. Hiroyuki Sumi (famous for his research on natto, fermented soybeans) showed that sweet potato honkaku shochu and awamori contain aromatic compounds that stimulate blood vessels to secrete clot-dissolving enzymes.

As Dr. Sumi noted in a 2016 Nikkei Business interview: “Our experiments confirmed that drinking honkaku shochu or awamori nearly doubles the secretion and activity of clot-dissolving enzymes t-PA and urokinase when compared with non-drinkers.”

Dr. Sumi suggests drinking oyu-wari—sweet potato shochu diluted with hot water. The warmth enhances aroma release and improves absorption. Even non-drinkers can benefit by inhaling the vapors as aromatherapy.

Have you tried shochu?

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/